Part 1: Do nerves get pinched?

|

What prompted this article was some discussion in the social media along these lines: "People don't get pinched nerves so we should not be telling patients they have one." Pinched nerves is an ambiguous and unfortunate term because it can conjure all sorts of negative connotations andemotions in patients with pain problems So here is a clarification in more scientific terms. |

"There is no evidence for stuck nerves so we should not be telling patients they have one."

|

Whether nerves get pinched is a very important question because we have a professional responsibility to be clinically accurate and make our explanations to our patients factual, which must include the evidence.

Hence, there are three parts to this article: 1. Do nerves get pinched? Here is some research that you should know about as it basically validates the idea that nerve roots can get pinched. 2. The statement "There is no evidence ...". Discussed is the idea that 'lack of evidence' is misunderstood and often used incorrectly to justify not doing something. Also, the decision to NOT do something can itself be based on a lack of evidence. 3. Integration of evidence This section discusses that integration of documented evidence is important but it has its limitations.

|

Clinically, it is imperative that the clinician searches for both supporting and negating evidence in an unbiased fashion so decisions are influenced primarily by what is found in the patient.

|

If 'stuck' means the nerve can't move adequately, then this is more complex. There is quite a lot of valuable research on this now in the form of ultrasound imaging of longitudinal nerve movement but I don't refer to it here as it's a large subject and validity comes into discussion, too much for here.

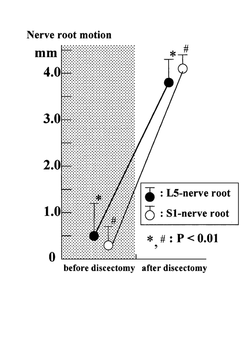

Instead, here are two examples of a stuck nerve, when it means loss of movement, alias 'mechanical impairment'. Clinical example: Athlete - hamstring injury and sciatic nerve I saw an elite athlete a while ago who had pain in the posterior thigh which co-existed with scarring around, and degeneration of, his hamstring tendon as it inserted into the ischial tuberosity, found on MRI. The slump test reproduced his pain and it changed with cervical movements, supporting a neural element to the problem. At surgery, the smart surgeon did a straight leg raise to observe behaviour of the sciatic nerve in the ischial region. Even after freeing it surgically by removing the scar tissue and manually mobilising it, it was noticed that the nerve remained tight, compared with what the surgeon had noticed in other patients with similar testing. The conclusion was that the nerve is intrinsically tight and just can't move normally. That is a stuck nerve. Lumbar nerve root There are certainly studies that show loss of lumbar nerve root movement in patients with radiculopathy due to disc protrusion. It has been found at surgery that the lumbosacral nerve roots lack movement when tested neurodynamically with the straight leg raise (SLR). When the nerve roots are 'freed up' surgically by removal of the disc protrusion and scar tissue, the nerve root movement improves, along with the intraneural blood flow and the neurodynamic test (SLR) response. In this study by Kobayashi et al (2003), the more restricted was the nerve root movement, the worse the clinical features, particularly the SLR. Before removal of the disc protrusion and adherent scar tissue, the S1 nerve root could only move in the foramen 0.5 mm on average. After release, this increased to 4.1 mm and correlated with improvements in nerve root blood flow, SLR angle and patient responses (See figure - left, from Kobayashi et al 2003, 2010). In this study, the nerve roots lost as much 85% of their excursion! That is a stuck nerve. Now that we have evidence for stuck lumbar nerve roots, how effective can neurodynamic tests be in diagnosis when compared with a gold standard such as MRI showing nerve root compression by disc protrusion? Majlesi et al (2008) showed that the slump test produced the sensitivity and specificity ratings below, when reproduction of clinical symptoms was used as the key diagnostic criterion: Sensitivity - 0.52 Specificity - 0.89 Positive likelihood ratio - 4.73 Negative likelihood ratio - 0.54 N = 77 If you think a patient does NOT have a neurodynamic problem Ask yourself - "Have I tested for it properly in my subjective and physical examinations and found negating evidence that outweighs any supporting evidence?". If you think a patient DOES have a neurodynamic problem Ask yourself - "Have I found supporting evidence in my subjective and physical examinations that outweighs any negating evidence, including: Subjective - radiating pain and pins and needles or numbness, muscle weakness and/or wasting. Medical tests - radiology, neurophysiology, surgical, haematological, metabolic, genetic Physical - neurodynamic test responses, nerve palpation and neurological testing?" SUMMARY POINTS 'Lack of evidence' is often used incorrectly to justify excluding a diagnosis. Lack of evidence is NOT negating evidence. Just as supporting evidence can implicate a diagnosis, negating evidence helps to exclude it. Clinical decisions are based on searching for both supporting and negating evidence, balancing the two. NEXT: Part 2 - "There is no evidence for that ..." -- REFERENCES Kobayashi S, Shizu N, Suzuki Y, Asai T, Yoshizawa H 2003 Changes in nerve root motion and intraradicular blood flow during an intraoperative straight-leg-raising test. Spine 28 (13):1427-34 See abstract Kobayashi S, Takeno K, Yayama T, Awara K, Miyazaki T, Guerrero A, Baba H 2010 Pathomechanisms of sciatica in lumbar disc herniation: effect of periradicular adhesive tissue on electrophysiological values by an intraoperative straight leg raising test. Spine 35(22): 2004-2014 See abstract Majlesi J, Togay H, Ünalan H, Toprak S 2008 The sensitivity and specificity of the slump and the straight leg raising tests in patients with lumbar disc herniation. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology (2): 87-91 See abstract |

Globally located seminars in evidence informed clinical neurodynamics. |

NDS Neurodynamic Solutions sends free updates on neurodynamics.

|